What is “Lean Cruise”?

From the late 1990s through the mid 2000s there was this mysterious feature enabled in some non-US V8 (LS1) engine software calibrations that was purported to improve fuel economy. Some of the aftermarket calibration product suites referred to it as “Lean Cruise” and what it did was it allowed the vehicle to operate at fuel mixtures leaner than stoichiometry (14.7:1 air to fuel ratio on non-ethanol gas) under certain light-load conditions (such as steady state cruising) – generally up to 17:1 or 18:1.

How does “Lean Cruise” improve fuel economy?

“Lean Cruise” has positive impacts on fuel economy, but not largely for the reason most people think. It's widely believed that running a leaner mixture means less fuel is being consumed, and hence the fuel economy improves. This is true, but it is by far the smaller effect versus another: reducing pumping losses.

Pumping losses occur, particularly on large displacement engines while the engine is under light load because a gasoline engine's power output is currently regulated by a throttle blade (though newer engine designs are beginning to use variable valve lift technology as an alternative). In the steady-state cruise scenario, the throttle blade needs to be mostly closed to maintain a specific vehicle speed. Because the throttle blade is mostly closed, the pistons operating on the intake stroke are literally fighting against the throttle blade to pull a full cylinder's worth of air in but cannot.

“Lean Cruise” reduces pumping losses because it requires the engine to operate with the throttle blade opened further than it would otherwise if it were operating at stoichiometry. The engine cannot generate power as efficiently at leaner mixtures, so the engine needs to be operated under a higher load at the leaner mixture. Naturally, the LS1 engine was a perfect choice to implement “Lean Cruise” on.

“Lean Cruise” is not allowed by US EPA / CARB regulations

“Lean Cruise” was only enabled in certain non-US software calibrations where the emissions standards allowed it. Running the engine at a leaner mixture increases combustion chamber temperatures and dramatically increases the amount of “oxides of Nitrogen” (also known as NOx) emissions. The other emission-related issue is that the catalytic converters used on modern day vehicles, (also known as Three Way Catalysts) require the engine management software to oscillate the fuel mixture between slightly lean and slightly rich in order for it to be able to do its job. TWCs cannot function properly if the fuel mixture is run in the ranges that “Lean Cruise” utilizes.

Newer engine designs lose the pumping losses benefit from “Lean Cruise”

Remember what we said about pumping losses? GM's answer to that issue was to solve it using two other technologies (though only one of which is relevant to the LF4): 1. Variable valve timing (VVT), and 2. Active fuel management (V4 mode on the V8 engines).

The LF4 enjoys a great benefit from VVT because both the intake and exhaust camshafts can be independently phased. Under light load cruising conditions, the engine control module (ECM) sets the camshafts for more “overlap”. “Overlap” is the amount of time both the intake and exhaust valves are open. By setting both valves to be open, instead of fighting against the throttle blade, the intake stroke can pull exhaust gasses back into the combustion chamber, thus reducing pumping losses with the added benefit of inducing Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) which is also beneficial for controlling emissions.

The other way VVT can help reduce pumping losses – a technique that is also used on the V8 engines, is by retarding the intake valve event such that it begins as late as possible after top dead center (ATDC). This effectively shortens the length of the intake stroke, and the engine spends less time fighting against the throttle blade.

Active fuel management (AFM) further reduces pumping losses by effectively shutting off 4 of the 8 cylinders (though newer AFM designs allow for shutting off up to 7 cylinders). It does this by disabling the camshaft lifters on 4 of the cylinders, so those cylinders are no longer fighting against the throttle blade. This feature doesn't exist in the LF4, but newer V6 engine designs like the LGW, LGX and LGZ all can disable 2 cylinders on the fly.

“Lean Cruise” was removed from OE software

“Lean Cruise” disappeared from OE software when the newer series of engine controllers was developed starting with the Gen IV V8 in 2005. In 2006, the L76 engine was introduced. This was a 6.0L engine that had VVT – the first of its kind. Later variants of the Gen IV V8s such as the L94 and the L99 used VVT primarily to improve fuel economy by reducing pumping losses.

It is clear that GM found better results with VVT than using “Lean Cruise” without having to maintain two different emissions standards and software calibrations for various regions.

Any modern “Lean Cruise” implementation would require some trickery

Because “Lean Cruise” as a feature hasn't existed in the operating system of the engine controller since around 2004, any implementation that attempts to mimic the effects of it would require some amount of trickery. It's certainly possible to calibrate the ECM to go into open loop fuel mode, and command leaner mixtures, but what are the possible side effects of that?

One is that many of the ECM's diagnostics won't run if the commanded EQ Ratio isn't 1.0 (stoichiometry) and in closed loop fuel control mode. O2 sensor self tests, EVAP purge events, sensor plausibility checks are just a few examples of diagnostics that require the ECM to drive the mixture specifically to test that the engine is operating properly.

Another IS that it cannot operate in closed loop fuel control mode if the commanded mixture isn't EQ Ratio 1.0. The fuel trimming system is designed to detect deviations in actual engine performance vs predicted engine performance, and provide a feedback-based correction mechanism.

One more is that the TWC (catalytic converters) cannot operate properly while closed loop fuel control is disabled, and the vehicle would produce emissions in excess of the limits allowed by the US EPA and CARB.

And last, running the engine at leaner-than-stoichmetric fuel ratios would cause combustion chamber temperatures to rise. Direct injected (DI) engines are already prone to a phenomenon called “stochastic pre ignition” (SPI) in which the fuel charge ignites too early. While the LF3 and LF4 seem to be relatively immune to SPI, it has been known to cause pistons to break between the ring lands on other GM turbo engines. The likelihood of an SPI event occurring would be increased by both increased combustion chamber temperatures and running a leaner mixture.

A lopsided trade-off between benefit and concern

As stated in the introduction, we won't be offering “Lean Cruise” on our products because we don't feel the trade-off between benefit and concern is a good one – largely because we have failed to find any substantial benefits at all.

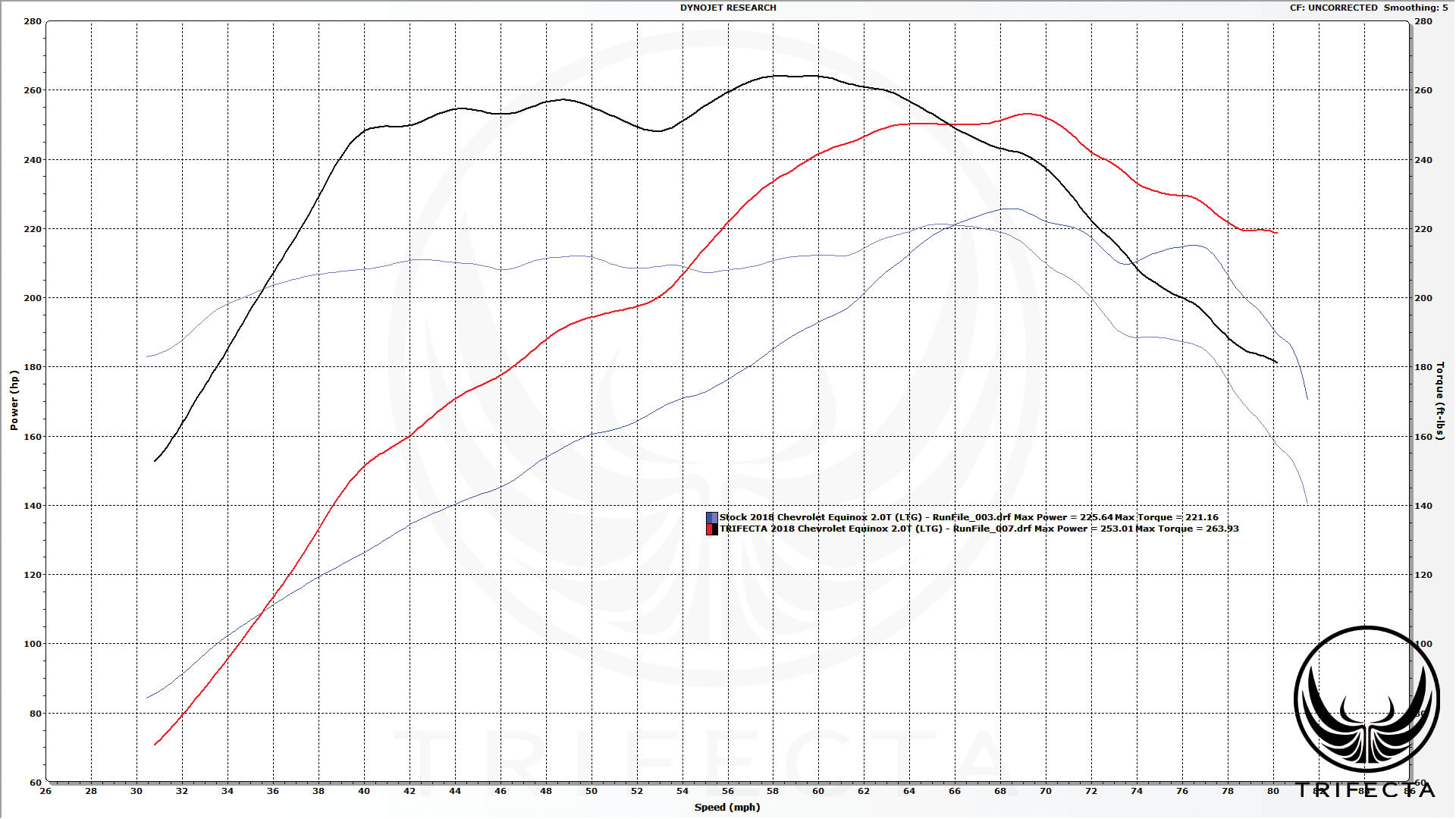

We have experimented with mimicking “Lean Cruise” in the newer engines and we haven't found any substantial fuel economy gains. We can't speak for claims that others are making but when we measured actual fuel consumption changes, the improvements were within the range of statistical noise. And this makes sense: when you consider the largest benefit “Lean Cruise” offers is reduction of pumping losses, the LF4's engine design itself (smaller displacement, turbocharged, independent VVT) does far more than “Lean Cruise” did back in the LS1 days.

We'd also challenge anyone who is using a “Lean Cruise” tune to check actual MPGs versus what is reported on the instrument cluster. If a modern “Lean Cruise” implementation is reliant on trickery, it stands to reason this would skew the ECM's ability to estimate the fuel economy as well.

Having said all of this, aftermarket engine calibration remapping is a dynamic process. We continuously challenge our previous notions in the light of what we learn along the way. It is possible one day we will make a discovery that changes the trade-off between benefit and concern.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.